August 2009

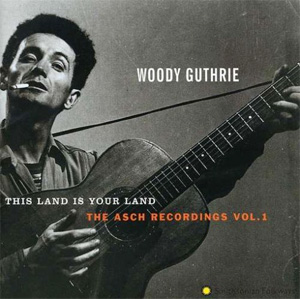

Woody Guthrie: A Songwriter for All

Seasons

As hard times

sweep across the American landscape, and throughout the human world, more broadly and

deeply than at any time since the Great Depression, some people have been dusting off John

Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath -- the classic novel about the travails of the

Joad family, all but one member of which abandon their Oklahoma dustbowl home, bound for

the purported Eden of California’s "fruit bowl." It’s also a good time

to dust off our recordings of Woodrow Wilson "Woody" Guthrie, a long list of

which are currently available, as well as the covers of his songs by Pete Seeger, Joan

Baez, Bruce Springsteen, and countless other excellent but less-well-known artists,

including Guthrie’s friend Ramblin’ Jack Elliott -- of whom Guthrie once said,

"He sounds more like me than I do." As hard times

sweep across the American landscape, and throughout the human world, more broadly and

deeply than at any time since the Great Depression, some people have been dusting off John

Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath -- the classic novel about the travails of the

Joad family, all but one member of which abandon their Oklahoma dustbowl home, bound for

the purported Eden of California’s "fruit bowl." It’s also a good time

to dust off our recordings of Woodrow Wilson "Woody" Guthrie, a long list of

which are currently available, as well as the covers of his songs by Pete Seeger, Joan

Baez, Bruce Springsteen, and countless other excellent but less-well-known artists,

including Guthrie’s friend Ramblin’ Jack Elliott -- of whom Guthrie once said,

"He sounds more like me than I do."

The familiar refrain of Woody Guthrie’s most famous

song, "This Land Is Your Land," is usually also sung as the opening verse:

This land is your land, this land is my land

From California to the New York Island

From the redwood forest to the Gulf Stream waters

This land was made for you and me.

Folk musicians and sing-along fanciers know the first three

verses, each ending with the refrain’s last line:

As I was walking that ribbon of highway

I saw above me that endless skyway

I saw below me that golden valley

This land was made for you and me.

I’ve roamed and rambled and I followed my footsteps

To the sparkling sands of her diamond deserts

And all around me, a voice was sounding:

This land was made for you and me.

When the sun came shining and I was strolling

And the wheat fields waving and the dust clouds rolling

As the fog was lifting, a voice was chanting

This land was made for you and me.

Of those three verses celebrating "our"

land’s richness and beauty, the second and third invoke a voice -- ostensibly an

inner one stirred by the singer’s experience of the land -- insisting that such

abundance and beauty must exist for all: By virtue of one’s humanity, one lives on it

and is humbled by it.

Hardly known, but published in the popular 1200-song Rise

Up Singing: The Group Singing Songbook (edited by Peter Blood and Annie Patterson),

and in Woody Guthrie Songs (edited by Judy Bell and Nora Guthrie, with an excellent

discography; TRO Songways Service), are the three verses that follow:

As I went walking, I saw a sign there

On the sign it said "No Trespassing"

But on the other side it didn’t say nothing

That side was made for you and me.

In the squares of the city, in the shadow of a steeple

By the relief office, I seen my people

As they stood there hungry I stood there asking

Is this land made for you and me?

Nobody living can ever stop me

As I go walking that freedom highway

Nobody living can make me turn back

This land was made for you and me.

Today, those three more-obscure verses are particularly

resonant. As I write, Bernie Madoff, 71, perpetrator of one of the biggest individual

pulled financial hoaxes to date, which wiped out thousands of people’s life savings

with impacts too far-reaching to be fully known as yet, has just received a prison

sentence of 150 years. His crimes might still be undiscovered had the financial markets

not crashed, beginning with the mortgage industry, which bases its earnings on the

land’s not belonging to you and me. However, tracts are always obtainable by

those who have plenty of what Guthrie calls the "do-re-mi" in the song of that

title (and innovatively covered by Ani DiFranco).

After Madoff’s sentence was handed down, one of his

victims said that what matters is not his punishment but what the government will do to

restore the victims’ money. Another said that since the exposure of Madoff’s

fraud, her life had been a living hell resembling a nightmare from which she can’t

wake. Others have been working multiple jobs, and some are living on food stamps.

Similar lives are now being lived by so many people

affected by the severe economic recession or depression we are currently enduring, and the

impacts on people in "developing" countries are so egregious that the news

industry’s focus on the Madoff case, and its treating of everything else as vague

statistics, downplays the situation’s enormity. These days, people at the

"relief office" may not be hungry; more likely they’re nurturing heart

disease, type 2 diabetes, or cancer from "supersize" portions of an

industry-serving American diet too rich in meat, dairy, eggs, fish, and sugar. But someone

has proven able "to turn them back on the freedom highway." And mortgage

foreclosures, whose primary cause before the crash was bankruptcy due to soaring medical

costs, have revived Guthrie’s question: "Is this land made for you and

me?"

By the time Woody Guthrie died, in 1967, having written

more than 1000 songs, the post-World War II G.I. Bill and the government "safety

nets," the latter part of the New Deal’s response to the Great Depression,

generated and maintained the largest middle class in our species’ existence. For the

vast majority, prosperity was taken for granted; even the comparatively poor and

disenfranchised were fed and sheltered.

It wasn’t that way when Guthrie’s father’s

real-estate business, begun in the first Oklahoma oil boom, went bust. Guthrie’s

sister was killed when a coal-oil stove exploded. His mother was put in an asylum, and was

later determined to have had Huntington’s disease, which eventually killed Woody

himself at age 55. When Guthrie’s father moved back to Texas, Guthrie "hit the

road . . . doing all kinds of odd jobs, hoeing fig orchards, picking grapes, hauling wood,

helping carpenters and cement men, working with water well drillers . . . I carried my

harmonica and played in barber shops, at shine stands" (American Folksong / Woody

Guthrie, Oak Publications, New York, 1961; cited in Irwin Stambler and Lyndon

Stambler, Folk & Blues: The Encyclopedia, St. Martins, New York, 2001).

Guthrie’s vagabond existence was like that of The

Grapes of Wrath’s Tom Joad, whom Guthrie portrays in a 17-verse tour de force,

with Joad’s name as the title, written "the night that I saw the moving picture The

Grapes of Wrath" (Woody Guthrie Songs). Unlike Guthrie, Joad flees the

hardships of Oklahoma with his family (though Joad later parts from them to escape the

law). The second verse of Guthrie’s masterpiece "Pastures of Plenty" gives

a concise lyrical picture of living the hard life without a safety net:

I worked in your orchards of peaches and prunes,

Slept on the ground in the light of your moon,

On the edge of your city you’ve seen us and then,

We come with the dust and we go with the wind.

Nor would Guthrie have joined in persecuting the

"illegal aliens" of our time, many of whom are among the estimated minimum

50,000 slaves in the U.S. today. Though not in the bonds of chattel slavery, outlawed now

for nearly a century-and-a-half, these workers are still dominated, abused, threatened

with death if they try to escape. They labor for almost nothing, as occurred for many

years after Emancipation because laws were not passed that would enforce the 13th

Amendment to the Constitution. As Guthrie’s much-covered "Deportee" puts

it,

The crops are all in and the peaches are rott’ning.

The oranges piled in their creosote dumps.

You’re flying ’em back to the Mexican border,

To pay all their money to wade back again.

Refrain:

Goodbye to my Juan, goodbye, Rosalita,

Adios mis amigos, Jesus y Maria;

You won’t have your names when you ride the big airplane

All they will call you will be deportees.

Some of us are illegal, and some are not wanted,

Our work contract’s out and we have to move on;

Six hundred miles to that Mexican border,

They chase us like outlaws, like rustlers, like thieves.

Note how Guthrie distances himself from the land’s

owners by addressing them with the second-person "you" and identifies with the

immigrants by calling them "my" Juan, et al. and adopting phrases of

their language. In "1913 Massacre," about a "murderous joke" by

"copper boss thugs and scabs" that killed 73 children of copper miners in

Calumet, Michigan, when labor had no legal protection and there was no recourse against

injustice and abuse by company owners, Guthrie starts by inviting the listener into the

scene, where "the miners are having their big Christmas ball . . . / Take a trip with

me in Nineteen-thirteen. / . . . I’ll take you to a place called Italian Hall. . .

."

I’ll take you in a door and up a high stairs,

Singing and dancing is heard everywheres.

I’ll let you shake hands with the people you see

And watch the kids dance ’round the big Christmas tree.

Guthrie understood how experiencing people as human beings

elicits empathy, and how people who make profit their top priority suppress empathy and

thus make it easy to cause others to suffer. The thugs in the song, hired by the bosses --

today we call them "corporate thugs" --

. . . stuck their heads in the door;

One of them yelled and he screamed, "There’s a fire."

A lady she hollered, "There’s no such a thing;

Keep on with your party, there’s no such a thing."

But the damage is done. "The gun thugs, they laughed

at their murderous joke, / And the children were smothered on the stairs by the

door." Now, a piano that we’ve heard a little girl play as partiers quieted to

hear her

. . . played a slow funeral tune,

And the town was lit up by a cold Christmas moon.

The parents, they cried and the miners, they moaned,

"See what your greed for money has done?"

Nor was Guthrie’s empathy limited to human beings --

witness the lullaby "Lay Down, Little Doggies" (doggies being old-time

cowboy slang for cattle):

Lay down, little dogies, lay down

We both gotta sleep on the cold, cold ground.

The wind’s blowin’ colder and the sun is goin’ down,

So lay down, little dogies, lay down. . . .

Here now we come to the end of our trail

Your hair, hide, and carcass to a stockyard I’ll sell.

I’ll see you in a tin can when you get shipped around

So lay yourselves down, little dogies, lay down.

Throughout, singer and cattle share their struggles and

experiences. "We blistered in the sun and we froze in the snow." Guthrie plainly

sympathizes with the animals, not with the "packinghouse town" they’re

headed for, or the stockyard where he’ll sell them.

Some comparisons between today and the Great Depression of

the 1930s are overblown. While today’s much-larger human population means that more

will suffer from any widespread catastrophe, as of June 2009 unemployment had reached to

only slightly below 10%; in the 1930s, it is estimated to have reached 25%. And back then,

little or no government safety net existed -- today’s programs were responses to the

suffering of those times. But the dynamics remain the same, and Guthrie beautifully

deciphers the human and moral components. He does not, as far as I know, distinguish

between actual persons, whom the Constitution and Bill of Rights exclusively aimed to

protect, and fictitious "persons" such as corporations, incapable of empathy or

any other experience, yet setting standards, creating incentives, and, since 1886, granted

the rights of actual persons through extra-Constitutional maneuverings (see in particular

Thom Hartmann’s Unequal Protection: The Rise of Corporate Dominance and the Theft

of Human Rights; Rodale Press, Emmaus, Pa., 2002). Hence his many references to bosses

and greed, but not to forces set in motion by humans but not themselves human.

Those old enough to have clear memories of the Great

Depression are now at least 75, and more likely 80 or older. In recent decades some of

them warned, as did some younger observers, about the dangers of financial deregulation,

to no avail. No matter who comes with the dust and goes with the wind, the line from

Guthrie’s classic ballad "Pretty Boy Floyd" -- "Some rob you with a

six gun and some with a fountain pen" -- is still true. Corporations now put pens --

and computers -- into hands trained not in factories, mines, and orchards, but in business

schools, and for the express purpose of putting the bottom line above any human or public

interest. One can easily imagine Guthrie asking What does anyone need an M.B.A. for --

aren’t they greedy enough without one? And perhaps deciding it stands for Money

Before All.

The word rob conjures images of weapons more than of

pen and paper, and this famous line also hints at the disproportionate attention paid to

violent crime over white-collar crime. The news industry’s having become part of the

entertainment industry -- "If it bleeds, it leads" -- leaves us on our own to

recognize where the big robberies are being attempted or perpetrated. Despite serious

behind-the-scenes warnings about "toxic assets," and books and articles decrying

deregulation and the massive and ever-increasing disparity between CEO and worker pay,

virtually all news-industry discussion of recent decades have amounted to boosterism for

the system and its institutions.

Woody Guthrie and those who follow in his footsteps might

not be heeded when needed -- nor, should we wish to know rather than blindly hope, might

the many useful books available. But the man who wrote "This machine kills

fascists" on the face of his guitar gave us art with practical implications for all

of humanity, rich in the images of lives simpler and, in many ways, more rewarding than

those lived today by most Americans. We need to recognize the reality celebrated in such

art so that we can construct a better future.

. . . David J. Cantor

davidc@soundstage.com

| "For a

Song" Archived Articles |

- November 2008 - It's All

Right -- Really!: Paul Simon's "American Tune"

- July 2008 - What You Got,

What You Want: Two Steel-Belted Tunes by "Those Rubber Brains from Akron"

- March 2008 - Intriguing

Tribute to the Man of Steel: "Superman’s Song" by Brad Roberts

- January 2008 - A Song for

All International Disasters: Warren Zevon’s "Lawyers, Guns and Money"

- September 2007 - Through a

Hole in the Air: "Democracy" by Leonard Cohen

- August 2007 - The Circus Is

in Town -- and Vice Versa: Bob Dylan’s "Desolation Row"

- May 2007 - Put Your Life on

the Line for Your Oppressors: Joe Strummer’s "London Calling"

- April 2007 - Pretty Tune,

Powerful Song: "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?"

- February 2007 - Welcome to

the Working World: Elvis Costello’s "Goon Squad"

- January 2007 - Pop

Sociology of the California Dream: The Beach Boys’ "I Get Around,"

"Fun, Fun, Fun," and "Catch a Wave"

- December 2006 - What's a

Daughter To Do? Family Values in the Traditional Ballad "Willie Moore"

- November 2006 - Here’s

to You, Paul Simon: "Mrs. Robinson" and Her Legacy

- October 2006 - Liberate or

Dominate? "Won’t Get Fooled Again"

- September 2006 - The Cost

of Freedom: "You Can’t Always Get What You Want"

- August 2006 - Loss and Hope

One Day at a Time: James Taylor’s "Fire and Rain"

- July 2006 - The Past is Not

Past: Elton John & Bernie Taupin’s "First Episode at Hienton"

- June 2006 - The Boss’s

Theme: "Born To Run" by Bruce Springsteen

- May 2006 - A Hymn to No

Religion: John Lennon's "Imagine"

- March 2006 - Dream,

Nightmare, or Both?: Neil Young’s "After the Gold Rush"

- February 2006 - A Hot One

for the Ages: The Doors’ “Light My Fire”

- January 2006 -

"Stairway to Heaven": Gold Beneath the Glitter

- November 2005 - All We

Really Have: "Redemption Song" by Bob Marley

- October 2005 - A Man

Ain’t Nothin’ But a Man: "The Ballad of John Henry"

- August 2005 - Up and Down

and Every Which Way: Joni Mitchell’s "Both Sides, Now"

- July 2005 - Outside the

Box: Talking Heads’ "Psycho Killer"

- June 2005 - Introducing

"For a Song" | Uneasy Listenin’: Bob Dylan’s "Blowin’ in the

Wind"

|